"Wait—Who Taught My Son the 'F' Word?"

What Wasn’t Supposed to Happen Yet

If you’re new to Raising Myles, Welcome!

I write letters to my newborn son, Myles, sharing my journey as a first-time dad and spreading the love I didn't experience myself. If you’ve been here before — thank you for coming back. If you’re new here, here are some good places to start.

My Wife’s Love Affair - It’s exactly what you don’t think

Dear Myles,

We do not curse at home, but damn, if I weren’t t too worried about what your mother thinks of me, our pastor, and all the Jesus-believers I know who probably curse on the low too (what up, SDA)—this is how I wanted to bust down the doors of the daycare we are paying a whole lot for, full of fire, fury, frustration, and ferocity, shouting, Who taught my son the F-word?!

That morning, we were getting you ready for school. I was in the kitchen cleaning up after breakfast while your mother was getting you dressed. This is our daily routine. We just grunt and point in the morning—too tired for anything else, too tired for verbs. “You food, me baby.” I cook, she finds clothes. I clean dishes, she dresses you. Obviously, we don’t actually talk like that at home (I don’t even know why I feel the need to say that).

But I do love hearing her talk to you when I am not even in the room. She says all the things I think every child needs to hear. And it is not the usual affirmation stuff, like “You can do anything you put your mind too.” No. Right now, if a stranger walked into the house and overheard the conversation, they might not even realize she was talking to a two-year-old.

“Tell me, what do you want to wear today? Can you tell me what we are going to do today, Myles?” No close-ended questions—just wide-open ones. And it is never, “Do you want this or that?” It’s, “What do you think about this or that?” That is open-ended too, because what matters is that your voice already matters. You’ve got options, a whole lot more than I had as a two year old.

Anyway, I am washing dishes when I hear it, but I am not sure. I try never to assume, because in this house there’s always a high probability that I’m wrong. By this point, you know I married up—I married someone much smarter than myself.

But then your mother called out, “Marc, you heard that?” And I knew this time was different. This time, I wished I was wrong.

I came into the living room, and she started explaining what my ears had heard but my eyes hadn’t fully processed.

“I don’t know,” she began, with just a touch of worry in her voice. “I was just taking off his shirt, and he pointed at himself and then said…”

She paused, then started spelling the word you had said just a minute before—the same one I was sure I heard from the kitchen.

She spelled it out, just like we do with all the forbidden words we never say in front of you:

C-A-N-D-Y,

N-A-P,

C-O-O-K-I-E.

And to be honest, I get a little emotional piecing together the letters as she mouths them slowly, reading her lips.

What. How? No, not this early, I think to myself.

I couldn’t have learned it this early. It had to be later.

I remember fifth grade. It was picture day. I always hated picture day. Why did we need to take these class photos every year? It was almost the same group of kids every time. I remember thinking, Do we really need another one?

My skin can still feel the itchiness of the thick sweaters I was forced to wear, and the prep your grandmother gave me to smile.

But now, because I know what I know, and apparently things only make sense when you become a parent, you’ll be doing picture day every year too, minus the itchy sweaters, of course.

So, we are lining up: shortest kids in the front, sitting criss-cross applesauce, tallest kids next, and the middle kids on the stairs. I’m lucky; I just made it onto the chair right at the end, not so lucky because that means I would be right next to where my teacher, Ms. C would stand.

And for the first time, we would be shoulder to shoulder. Ms. C was the kind of teacher who was so beautiful but so mean—in my fifth-grade boy logic, that made her ugly. Looking back now, I realize Ms. C just cared. But she was the kind of teacher who’d call your house when you did wrong, and on parent-teacher conference night, she’d make your grandparents’ belts start to uncoil right then and there.

But surely, on picture day, she’d smile—just this once in her life—and not in the way she really wanted to tear us up.

She walked over to join me after telling all of us to stay close and make sure we smiled. Then she saw me—looked me up and down in a way I still can’t forget, even twenty-something years later.

She fixed her gaze at the base of my chair, like I shouldn’t be there. And then, for some reason, she pulled at the seams of my pants.

I was confused. It couldn’t be because I was sagging my pants—because I’m Haitian. There is no such thing as sagging when you’re Haitian. No, we wear our pants high— higher than the pride of Haitian mothers who can dish jokes faster than they can kwit diri, but are slower to remind you how much they love you more than the belt that’s on fire. Because I would have caught fire if my pants dared to drift below my waist.

Is it too high? I thought to myself. Ms. C pulled my seams with such vigor, it made the chair I was standing on wobble. Then her eyes followed up my seams, skipped my waist, and locked into my eyes with a look of confusion and a tinge of disgust. And then she said it: “Why are your pants so tight?”

That was exactly the first time I felt the weight of the words we heard you say that day—the same words we never taught you, the same words your mother spelled out:

F-A-T.

“Where did you learn that word, Myles?” I asked so softly that the breath still attached to your name barely escaped my mouth. I tried to mask what I was feeling inside so you wouldn’t pick up any clues that this word was not okay.

But inside, like most people who can’t easily process sadness and pain, my body, my brain really wanted to run up to your school that morning with some real fire and demand answers.

Because you’re too smart. It’s no coincidence you said it as soon as your mother took your shirt off. You already know your ABCs, 123s, shapes, and colors in two languages. You know more words than you can count—literally.

Because it’s too soon. You are only two. It happened to me when I was ten.

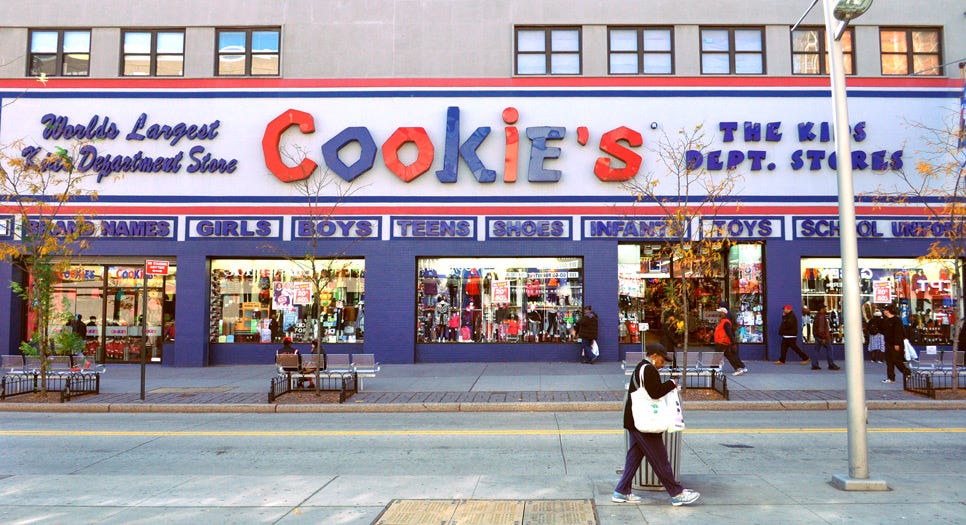

I remember when we first got those pants. We were in Flatbush, Brooklyn, heading to Cookies. We went every year.

I remember the first time my mother, your grandmother, told me we were going to Cookies—I was excited. What kid wouldn’t be? A store named Cookies sounded like every child’s dream.

But to my dismay, this store didn’t sell cookies. It didn’t even smell like sugar. When we finally reached the corner where Cookies stood, I looked up and read the sign—small font, right under the big red and blue letters that spelled out Cookies: Girls, boys, teens, shoes, infants, toys, school uniform.

That was the first time I learned what false advertising was. We weren’t here for sweets, we were here for school uniforms. And ever since that day, I hated shopping for school uniforms. I hated back-to-school season.Even now, the very beginning of August, the sight of a back-to-school aisle still makes me a little nauseous. My body just knew school was coming (hard to believe after all this I still became a teacher).

So here we are, another year, another August, in a store named Cookies, with no cookies in sight, and no no cake either.

I’m trying on pants after pants, and nothing fits. And to me, I’m not thinking it’s me—I’m thinking maybe my mom doesn’t know my size. I don’t know. I’m in the fifth grade. What fifth grader knows his size?

I’m thinking maybe this store should really consider selling cookies, because clearly if you don’t have my size why are you in business?

We keep walking.

And then I find a pair of pants—me, not my mother. They feel different from the others. A little tougher, firmer to the touch. And they have a logo that grabs my attention the moment I see it: the silhouette of a big dog. Not the kind of dog I had ever seen in Brooklyn. Na, this was a dog I had only ever seen on TV.

Underneath the silhouette, in bold letters, it said: Husky.

I grabbed the first pair from the stack, ignoring the dimensions. Like I said, I didn’t know my size anyway.

For the first time, I went to the dressing room, and when my mom called out, “How’s it fit?” I smile and tell her, “It’s good.”

They were not too long, not too tight. I did not have to sqeeze my thighs so much into them like my other pants. And best of all—I had never seen another kid at school wearing Husky.

They ain’t never heard of no Husky, I thought to myself.

Maybe Cookies did not need to sell sweets after all.

So when the teacher pulled at my pants, I knew it wasn’t because my mom didn’t know my size, or because I was a fifth grader. It was because I was fat.

Or at least, that’s how it felt.

It wasn’t until later that I learned Husky wasn’t just a brand—it was a size. A category. It was made for kids built like me: shorter, stockier. And back then, “stockier” just meant fat.

And it’s one thing for a fifth-grade boy to wonder if something is wrong with his own body— It’s a whole different thing to have that suspicion confirmed by a teacher.

Looking back now, maybe she didn’t mean it the way it came out. Maybe she didn’t know better. But over twenty-something years later, that’s still how my body remembers it.

And that’s why I spent years playing sports, going to gyms, lifting—trying to make sure no one would ever make me feel like that again.

Because even though nothing was ever wrong with the way I looked, no one taught me early on to love it.

No one told me I was fearfully and wonderfully made.

No one told me that even if my thighs had to squeeze into pants sometimes, it didn’t mean something was wrong with me.

So when I saw your mother spell those words out, I almost wished it had been an expletive instead.

I wish this had not happened so soon.

Because you are only two.

I want to sit down with everyone in our lives, every teacher, uncle, grandparent, aunty, and ’nem—and let them know:

We need to protect you at all costs.

We need to shield you for as long as we can.

Because I know society does not want to believe it, but boys—boys like you, and boys like me—are fragile.

And if we do not recognize that boys need more love, more patience, and yes, more hugs than their sisters

we risk doing more harm than good.

At that meeting, I want to remind them of all the things we have to prepare you for in a world that may never fully receive your beauty.

Because no matter how much we remind you at home that you are handsome and brilliant,

someone out there can pull at any one of those seams

and undo everything we are building.

My son,

Even though you have only said those words once—and I do not know if you picked them up from daycare,

or from the aunty who lovingly calls you her little fatman—

I want you to know:

You are not fat, but even if you were, you’d still be fucking beautiful.

I love you, and there is nothing you can do about it.

Love,

Daddy

If you can’t commit to a monthly subscription, but still want to support Myles’ college plan, here is my Buy Me a Coffee page.

And if you are on Substack, please restack this letter and recommend it so I can share this love with the world.

Let me know your thoughts:

What’s a moment when your child surprised you with something you never expected them to say or do?

What’s one “parenting challenge” that caught you completely off guard?

When was the first time you remember feeling insecure about your own body or appearance? What triggered it?

Who or what has most shaped your understanding of respect and boundaries growing up?

Too many GiFs?

Want more of Myles’ Letters?

These are Subscriber’s favorites:

Myles met his Grandfather in Brooklyn, NY

Read about Our first Father’s Day.

A video about beautiful backgrounds: Tell Them Where You're From.

Read about My Wife’s Love Affair - It’s exactly what you don’t think

Have you ever been Cooking in the Bathroom kind of tired?

Check out Carrying the Gift, Holding the Love

I'm not a parent, however, I will say that you're doing so well<3. secondly, there's never too many gifs!! They are FIRE.

You have captured so perfectly one of the hardest challenges of parenting - when the outside world starts influencing your child, teaching them words to use about themselves and others, changing the way they see themselves. I was so intent upon not criticizing my own body in front of my daughter. Women are so conditioned to want to be smaller that my slender son's struggles were not immediately apparent to me. The locker room admonition to "eat a sandwich, kid" haunted him but it took me too long to understand how being skinny could possibly be bad. Like you, those experiences sent him to the gym with a mission. Not a negative thing, but still I'll always regret not understanding sooner what he was dealing with. And then menopause came along for me with the shock of a new body and suddenly I had broken all my rules about negative body talk in front of my daughter. This is such hard stuff. And you're right, it starts way too early and it doesn't end. I'm still working at all this body image stuff with kids who are 20 and 23. We're still having conversations about it, which is both sad and really great. Like so much of parenting, it's a marathon, not a sprint. Thanks, as ever, for shining a light on the important stuff.